by Fran Flutter

Originally printed in a 2012 newsletter from the Ocean Cruising Club.

Housing was in short supply post World War Two. It was quite a popular option to live aboard one of a variety of vessels now surplus to requirements – motor torpedo boats, Thames barges, etc.

My parents decided to buy a boat that they could sail and, knowing nothing, were fortunate in choosing a 14 ton Hillyard. In 1950 they planned to emigrate to Australia in their second yacht, a composite- built ketch with elegant overhangs but, caught out by an autumn storm in Biscay, they were forced to return to the UK.

My parents decided to buy a boat that they could sail and, knowing nothing, were fortunate in choosing a 14 ton Hillyard. In 1950 they planned to emigrate to Australia in their second yacht, a composite- built ketch with elegant overhangs but, caught out by an autumn storm in Biscay, they were forced to return to the UK.

In 1958, with two daughters aged nine and five and a very different yacht, they set out on an Atlantic cruise. Several people expressed doubts as to the wisdom of taking young children to sea on grounds of personal danger and disruption to education.

My parents thought we should sink or swim together, and the Parents’ National Education Union provided excellent coursework – morning lessons became very much part of the routine. Parents worked through the course and periodically set tests and essays which were posted back for marking. Return post was sent c/o Consular Agents and Barclays Bank, which had branches in all sorts of places, and I cannot remember anything going astray.

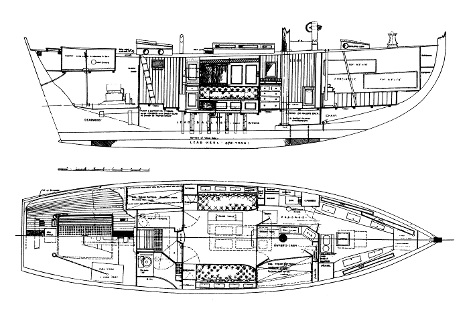

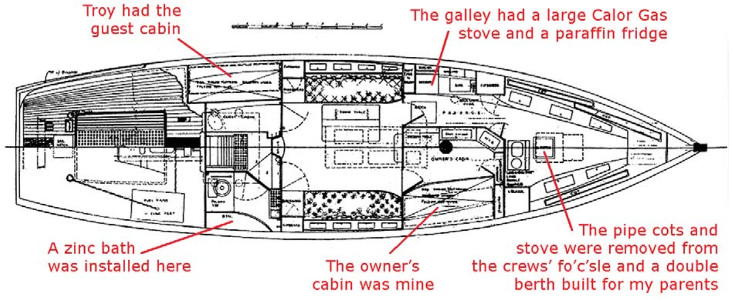

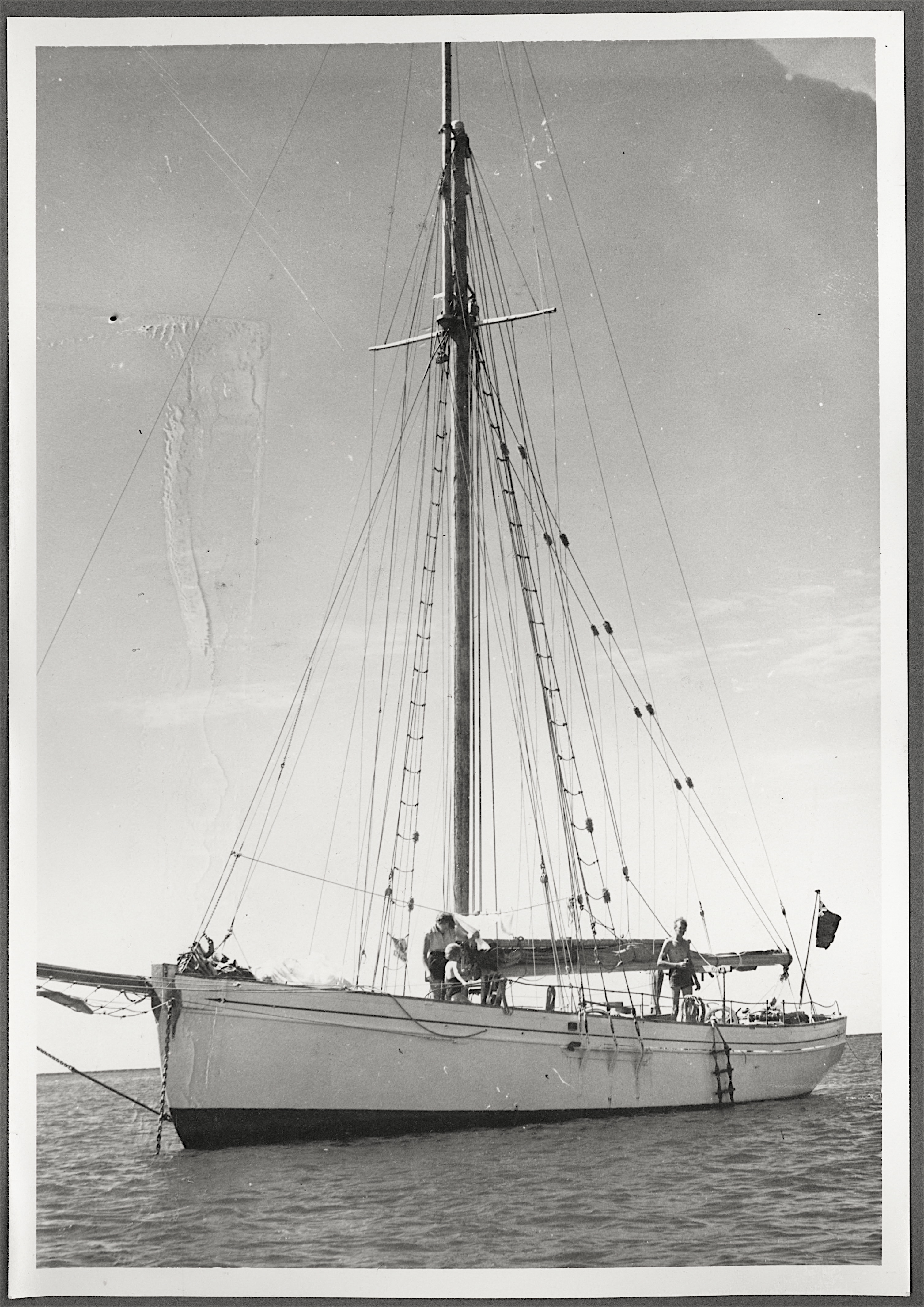

Tally Ho had been designed by Albert Strange in 1910, and was designed to keep the sea and take her first owner fishing. At 48ft on deck and 29 tons Thames Measurement she made a comfortable sailing home for a family. My father shortened the boom and replaced the wicked iron tiller with wheel steering, but she kept her 12ft bowsprit and powerful gaff cutter rig.

We left Falmouth in July with time in hand to explore the route south to the Canaries. It must have been a great relief to round Cape Finisterre and anchor off Corcubión, with Biscay safely astern. A strong southerly gale brought an influx of fishing boats seeking shelter and meant an anxious night on anchor watch, pumping the pressure lantern on the forestay every few hours.

Once the wind veered to the north we sailed for Vigo. The yacht club basin was tight for space and our entry untidy as the elderly petrol/paraffin engine died. Its unreliability caused problems throughout, resulting in occasional embarrassment but also making friends for us – people love to offer advice and practical help.

In Leixões we were taken up by a family in the port trade. They took us inland to their estate and showed us the beautiful city of Oporto – their hospitality made us feel very welcome in Portugal. This was followed by a thorough exploration of the city and environs of Lisbon. Our base was in the Doca de Belém where we moored near the famous Jolie Brise, winner of the first Fastnet Race in 1925. Tally Ho had won the same race in 1927, so was not outfaced.

Money was a constant pre-occupation. The miserly Foreign Travel Allowance of £50 per person, per year, had to cover all day-to-day expenses and stretch to unexpected ones, too. As Gibraltar was in the sterling area it was on the itinerary of most British yachts. We were berthed in the submarine pens, not far from the T-class submarine Tally Ho! The Navy swept my parents up into their social whirl and I remember tea in the wardroom for us girls. We still have the ship’s plaque they gave us.

It was a short sail to Tangier, where they did not know what to do with us. Eventually they shoe-horned us into a berth between two Fairmile motor launches, the cigarette smugglers of the day. The port had a bad reputation for thievery, but the watchmen on either side kept such a good eye on each other that we were secure as well. Further along the Moroccan coast we visited the commercial port of Casablanca, where I remember being squashed on the backseat of an overloaded Citroen DS19 as some French journalists demonstrated its revolutionary suspension with some fast cornering.

Then, as now, Las Palmas on Gran Canaria was the departure port for most yachts crossing the Atlantic. Like Gibraltar, this was a place where voyages often came to a premature end, leaving yachts lacking crews and crews looking for onward transport. There was a shifting population of laid-back characters, and a lot of partying. My grandparents arrived to see us, having travelled from England on a Spanish emigrant ship. Their pleasant hotel and the relaxed pace enabled them to ignore the prospect of the return journey. We all had an enjoyable time of trips and meals out, including my 10th birthday lunch.

Las Palmas wasn’t all fun, however, as the serious business of storing up and preparing the boat had to be fitted in. We had set out well-supplied with basic tinned food like corned beef and sardines, bacon and butter. Now dozens of eggs were dipped in boiling water before being dried and stowed. Fresh vegetables and fruit came from the market, not forgetting a stalk of bananas. In early November, yachts began to leave.

My father had had twin headsails made, to be poled out with booms attached to the capstan on the foredeck. The balanced rig made steering downwind easier, but someone was always needed on the helm. I loved being left on watch in the early evening, giving my parents a chance to enjoy a sundowner. They stood five hour watches overnight. The crossing took 33 days, including a five-day calm. The inflatable paddling pool was popular in the heat, water sloshing as we rolled.

We made landfall on Barbados in mid December, gladly recognising familiar boats in the anchorage in Carlisle bay – I believe about twenty yachts crossed that season. At last we could swim in the sea! In the mornings, they swam racehorses off the beach.

After a jolly Christmas in Barbados we sailed downwind to Bequia for the New Year. It’s hard to imagine just six yachts in Port Elizabeth. A local lady (also named Elizabeth) baked bread daily in an oil drum on the beach, and came aboard one evening to make a wonderful lobster and rice dish. The charter parties sometimes paid for steel bands to row out and play, which we could all enjoy. There was a wet and lively trip across the Bequia Channel on a local cutter to visit the market in Kingstown, St Vincent. It was an effort to leave, but other islands called. We sailed south to Grenada, the Spice Island, and unspoiled Carriacou. Heading back up the Grenadines, we were in Bequia again for Carnival, with every able body dancing for hours. In St Lucia, before the causeway was built at Rodney Bay, Pigeon was a proper island. A retired actress hosted lobster dinners there – if she liked the cut of your jib. We felt privileged to be allowed ashore.

Our stay in Martinique was memorable for two events. First my father managed to drop the anchor into an oil drum and was taken aback to find Tally dragging for the first time. Then my mother had a large bundle of linen laundered ashore and crisply ironed, but on the row back to the boat our folding Prout dinghy gradually filled and sank as the canvas gave in to the abrasion caused by coral sand.

English Harbour on Antigua was our last port in the West Indies. The Nicholson family ran a well-established charter business based there, but had only begun to reclaim the Dockyard buildings and there was plenty of room to lie stern-to amongst the fine, large yachts. Here we said goodbye to several of the crews we had met along the way, now friends to be looked out for wherever sailors gather.

ate in April 1959 it was time to head north towards Bermuda (my father had once had to make a square-search in a plane to find this low-lying patch of reefs) before turning eastwards across the Atlantic. It was disagreeable to leave the steady climate of the Trades for the Variables, and with the engine out of action again it was a slow passage. No-one wanted to go home. However, I loved the Bermuda islands with their Parishes, trim white-roofed houses, wonderful beaches and hospitable people. There was even a supermarket, our first! We were towed to Hamilton from St George’s Harbour and were lucky to see the skiffs racing. A kind family donated a big pile of Schoolfriend and Bunty comics for the voyage home.

The plan was to sail directly to the UK, as my father’s sabbatical from a small (and now long defunct) airline was a bit stretched. A series of gales with rough, confused seas took a toll on the boat. The fidded topmast crashed onto the deck, and the rudder stock could be seen working under the strain. Food supplies were also running low, so it was a relief when a dorado took the hook – fishing had not been a success until then.

The decision was made to stop at Faial for repairs, and a watch was set for the charted light. No light appeared – it transpired that an eruption 18 months earlier had changed the shape of the island and largely buried the lighthouse! In daylight all became clear and we made for Horta. Tally Ho needed to be lifted onto the quay to remove the rudder, and luckily there was a steam-powered crane available. (It was still there in 1980). My parents were greatly helped in making the necessary arrangements by the owners of the Café Sport and the employees of the Cable and Wireless Company. The work was swiftly completed, paid for after a flurry of telegrams to England, and the boat re-launched.

We had an uneventful last leg home to Falmouth, before sailing up-Channel to the River Hamble, where we lived aboard until I was 18. Winters were spent in a mud berth at Moody’s, while in the summer we had a pile mooring on the river. We never took Tally Ho cruising again, but my parents became early members of the Ocean Cruising Club and I found a way of life.